The Game of Globalism

Some words on the EU's "Global Gateway" and China's "Belt and Road Initiative"

John Martin, The Fall of Babylon, 1819

Yet I wondered fancifully if he had seen more clearly than they did, had sensed the threat which my presence implied – the approaching disintegration of his society and the destruction of his beliefs. Here especially it seemed that the evil that comes with sudden change would far outweigh the good.

Wilfred Thesiger, Arabian Sands

What is the Global Gateway?

On December 1st, the European Union unveiled its plans for a grand development of international trade and infrastructure, announcing that it would dedicate a vast sum of €300 billion over the next six years to various projects aimed at enhancing European supply chains. This initiative, called Global Gateway, will aim to provide grants, loans and guarantees to nations to help them develop their digital, energy and transport links. As with all projects of this nature, they are billed as selfless efforts to achieve vague ideas such as the global community; the EU commissioner for international partnerships, Jutta Urpilainen, stated that this will “build a new future for young people”, whatever that means.

In reality, the Global Gateway is being developed due to fears that the EU’s crumbling trade links will cause it to lose out in a future dominated by China, which has been undertaking their own large-scale investment project since 2013, called the Belt and Road Initiative. This initiative refers to a mass strategy launched in 2013 by Chinese president Xi Jinping which is attempting to connect the infrastructure of the Silk Road Economic Belt with the trade capabilities of the twenty-first century Maritime Silk Road in an attempt to increase the global creation of “shared value”. Shared value can be described as:

policies and operating practices that enhance the competitiveness of a company while simultaneously advancing the economic and social conditions in the communities in which it operates.

Michael Porter and Mark Kramer, in the Harvard Business Review article Creating Shared Value, 2011

The Belt, a vast expanse of interconnected railway and transport lines, pipelines and power grids prevailing through the countries situated on the old Silk Road trading routes of Asia, the Middle East and Europe, is being developed to flourish with the coupling of the maritime pathways, designed to link the Chinese coast with Europe and the South Pacific through the Indian Ocean and the South China Sea. The scale of such an initiative offers a seemingly win-win scenario for all involved, with China alleging up to 150 countries have already signed up for involvement, with overseas loans already totalling more than $90 billion by the first half of 2019.

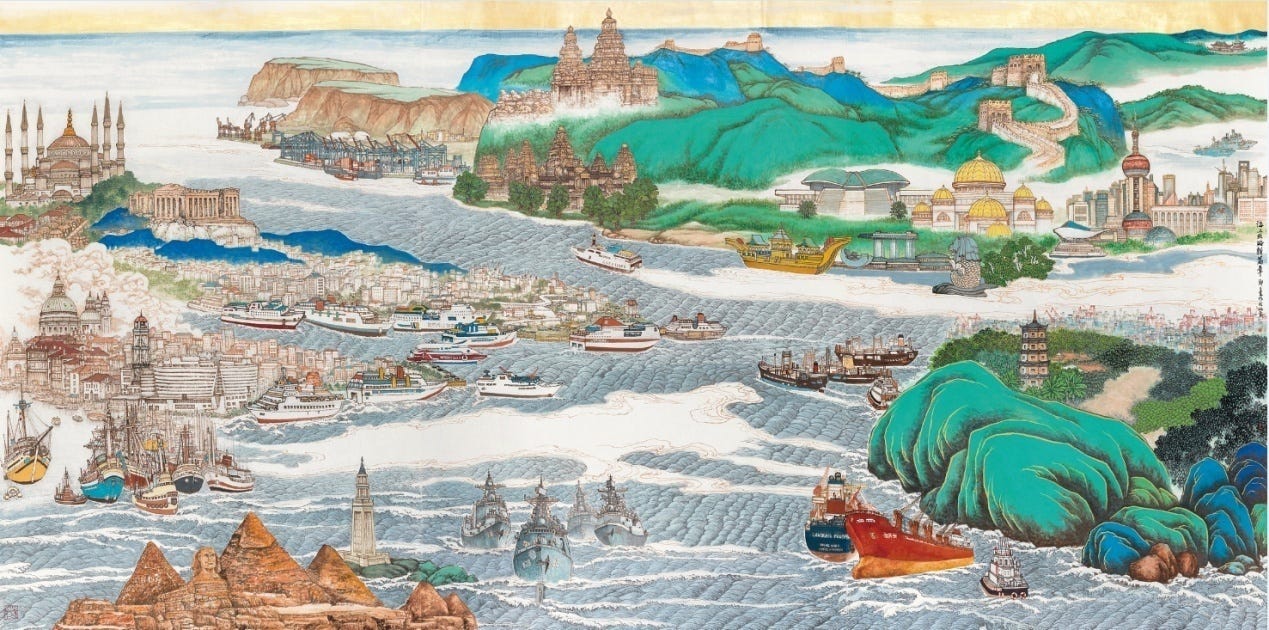

Illustrated map depicting the journey of the Venetian merchant Marco Polo (1254 - 1324) along the silk road to China

With developed and thriving economies existing at each end in Europe and East Asia, the BRI seeks to assist those countries encapsulated within its central region, catalysing their already large potential for economic development. However, since its advent, many countries have now become sceptical of the initiative and the potential dangers which may arise from creating a unified economic bloc in the east, with western powers harbouring doubts about a potential coagulation and subsequent weaponisation of eastern ideological forms, leading to the EU creating what EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen calls a “true alternative”, a notoriously trustworthy source.

Do They Really Want to Help?

This poses the question of whether or not the BRI is a genuine attempt at scaling up the creation of shared value globally or if it is simply the utilisation of hyperglobalisation and a shared goal to accentuate the economic and cultural power of the initiative’s driving forces. If that is the case, then the EU’s alternative cannot be seen as simply a good and moral substitute, but rather a desperate attempt to grab the reins of future hegemonic control.

As of 2017, China has maintained a relationship with 16 different countries located in central and eastern Europe (the CEE countries), all of which the proposed and currently existing trade routes of the BRI pass through, indeed being China’s only routes into the rest of the European market. Eleven out of sixteen of these CEE countries are members of the EU which, with the EU currently being the largest trade partner of China, effectively stations the countries in the region as clear entry points to the European Common Market for the BRI. Importantly, this shows that the European countries involved, typically post-socialist capitalist economies, are more economically developed than many other regions which China endeavours to partner with. Through this, China could effectively increase its production capacity, potentially facilitating a move away from supplying typically low-end products to integrating entire manufacturing supply chains in countries along this new route.

Naturally, this idea of added competition from China in many different markets has made EU states less optimistic than they originally were about the initiative, as it moves away from simply expanding and improving trade routes to facilitate free trade to effectively redistributing a share of market control to China. This is a large reason for the EU’s current plans, as not only do they want to avoid losing out on trade, but they don’t want their member states to develop closer ties with an outside force arguably stronger than the EU itself.

Zheng Baizhong, A New Chapter of the Maritime Silk Road, 2017

Many Such Cases

One notion which has made EU states less optimistic about the BRI is the lack of Chinese-backed green projects which have been created since the initiative was announced. Instead, Chinese focus has been on the advancement of infrastructural construction in order not only to ease their own industry-based overcapacity issues. This is partly why such a large focus of the Global Gateway has been on clean energy: there are plans to eliminate barriers on the international trade of hydrogen, alongside providing €3.5 billion in grants to boosting renewable energy production and increasing energy efficiency in Africa. In addition to this, the EU has also stated the desire to provide €4.6 billion towards developing sustainable transport links, such as a trans-Mediterranean network to link the bloc with North African countries.

Moreover, since CEE countries are still in need of large infrastructure projects and, importantly, investors to finance them, the EU is wary that China will grasp the opportunity to not only invest in advancing the infrastructure of these countries but also exporting the means of construction from its own industry in order to avoid overcapacity issues. This creates a worry that there may be a potential reintroduction of regional and geographical tensions as local workers and companies along the belt and road may be seen to lose out. Additionally, although investment and dialogue are free flowing to an extent in networked capitalism, labour is not. This may create problems as capital, both human and otherwise, is relocated from previous focal centres to focus on other projects within the initiative, potentially creating tensions between different cultural groups.

Furthermore, it is now widely accepted in certain spheres that China has an esoteric agenda for undertaking the BRI, making it a major threat to the existence of the EU. As well as the initiative with the CEE countries, China has also been working on the establishment of regional cooperative partnerships with Mediterranean and Nordic nations, which would effectively turn Sino-European relations into a series of regional talks. If such regional cooperatives thrive, then the purpose of the European Union and its common China policy would become diluted and diffused, with each region opting for different bilateral agreements to suit their own specific needs. Such a development would spell the end for Brussels' dominance over European states, giving further weight to China's mission to become the leading global power.

A Last Gasp

The UN Conference on Trade and Development's 2017 Trade and Development Report highlights many developmental issues with the modern world, citing the prevalent system of neoliberalism and the resultant hyperglobalisation as the main causes. In aiming to solve these problems, the report begins by detailing the need for a “globally coordinated strategy of expansion” focusing on the necessity of all countries involved in their vision of a “global new deal" at least being given the opportunity to benefit from growth in both domestic and foreign markets. The report argues that a revival of global demand needs to be formulated and cites the BRI as one of the more ambitious methods currently in planning for a sustainable form of globalisation.

Ultimately, the main reason the EU has now turned against the Chinese initiative is because it feels as though it is losing out. A 2017 report by the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs applauded the BRI as being of paramount importance to global development, one which would hopefully give the opportunity to expedite the achievement of the UN's Sustainable Development Goals; this is the sort of accolade the EU wishes to have. In a world still rife with Covid, the EU’s supply chain vulnerabilities have been highlighted for their ineffectuality.

The Global Gateway can be seen as nothing more than a desperate attempt at not getting left behind.

We used to leave them in peace. If they were called on, it was to get them to come and die in the towns, in the factories or in a war. Why have we suddenly developed a need for them, when they have no need of anything? What do we want them to serve as witnesses of? Because we'll force them to if we have to: the new terror has arrived, not the terror of 1984, but that of the twenty-first century.

Jean Beaudrillard, Cool Memories

Until we speak again,

AJP