Hasui Kawase, The Pine Island in Night Rain (Mitsubishi Mansion in Fukagawa), 1920. The Mitsubishi Group is currently responsible for Japan’s largest bank, trading company and defence contractor, among other entities.

When you look at the world with knowledge, you realise that things are unchangeable and at the same time are constantly being transformed.

Yukio Mishima, The Temple of the Golden Pavilion

What Happens Behind Closed Doors?

From the advent of the Empire of Japan, which arose in the second half of the nineteenth century and transformed the nation from an isolated archipelago at risk of colonisation into what would become a powerful state, the Japanese economy was predominantly controlled by what are known as zaibatsu. These zaibatsu were pyramidally-structured business groups which were industrially diversified and often controlled by a single family, creating large national monopolies which endured across generations.

The largest of these business groups had political parties associated with them which, due to their considerable influence, produced several of the country’s Prime Ministers. Some of the most prominent of these zaibatsu are still globally recognisable names today, such as Mitsubishi and Mitsui, and have now been operating in some form for almost four centuries. By the beginning of the Second World War, the four largest zaibatsu had close to 50% control of the nation’s machinery and equipment industries and controlled 70% of the commercial stock exchange.

However, it was the war, or more accurately its victors, which was to be their downfall; the zaibatsu were abolished, with a large portion of their production capabilities being nationalised to assist with the war effort, and many stocks in component companies which had existed antebellum were redistributed after the war due to an active effort by the allied occupation. Over the next twenty-five years, through the development of cross-shareholdings and large mergers and acquisitions, these zaibatsu developed into the keiretsu groups: structures consisting of large core firms with myriad affiliate companies allowing for risk sharing and preferential treatment at the benefit of member firms.

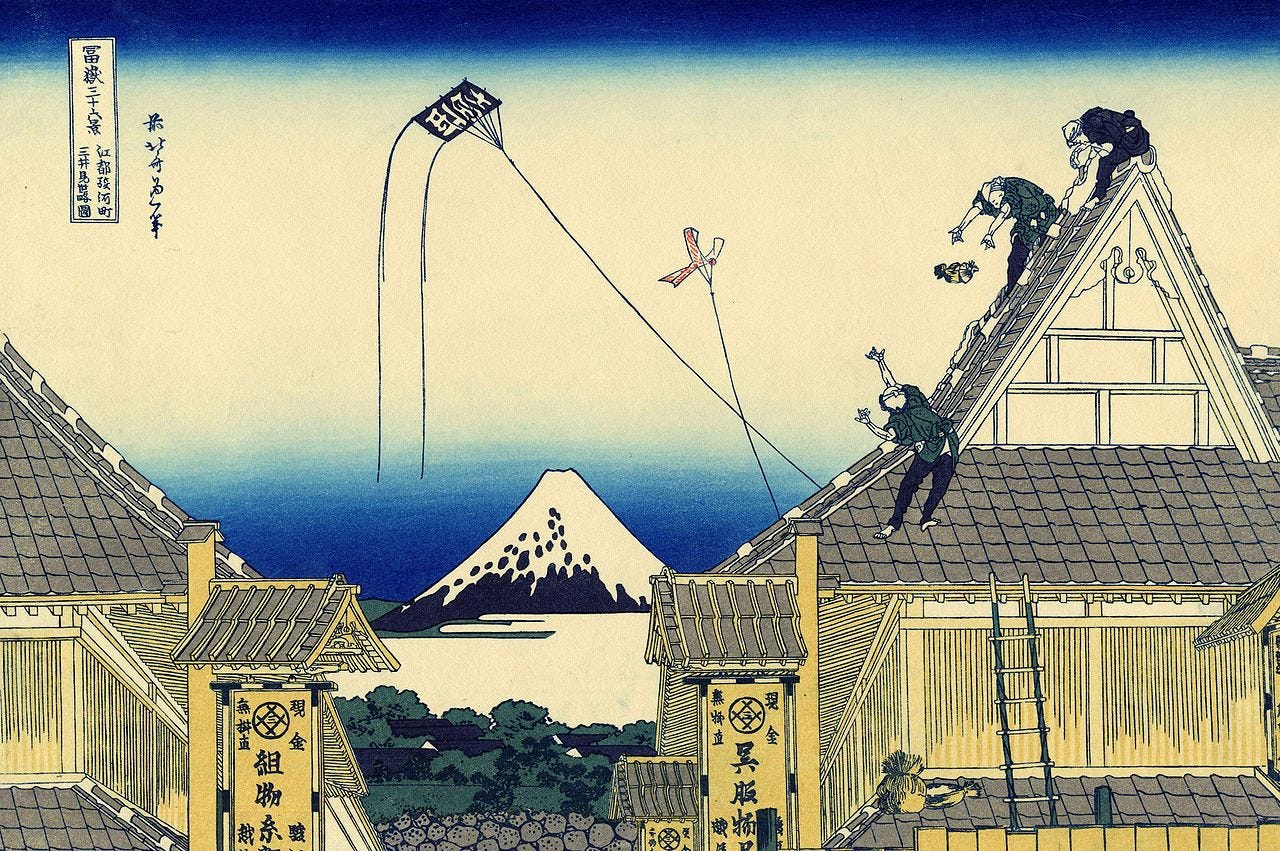

Hokusai, A sketch of the Mitsui shop in Suruga in Edo, from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, c.1830-1832. Mitsui developed into being one of the largest corporate groups in the world.

Typically, the keiretsu groups had notable similarities in their management models which differentiated them from other nations, in particular those global players in the west. Notably, one major differentiating aspect of these business groups was their corporate governance; evolving from the notion of one family or particular group being in control of affairs, the keiretsu developed a ‘behind closed doors’ approach, being discreet with publication of assets and liabilities, and having large, intertwined boards, all contributing to a lack of transparency.

Do Traditions Hold You Back?

Such corporate governance, while allowing for the minimisation of risk for affiliated firms, often leads to false valuation of firms and their stocks, and, subsequently, these Japanese business groups are notorious for seeing huge globally significant scandals. One notable example of this is the scandal surrounding optical equipment manufacturer Olympus’ loss-concealing practices in the early years of the 2010s, in which they hid over 117.7 billion yen (~$1billion) of investment losses.

During the 1990s, Japan was facing somewhat of a “lost decade”, being unable to adapt economically to the developing global big business revolution and the push towards globalisation. Steadily, throughout this time, the keiretsu had begun to diminish, with their associated management systems evolving drastically to incorporate a more globalised economic approach. This has been developing consistently in recent years, but has become exacerbated by the effects of consecutive waves of lockdowns staggered across many countries, shocking the historic foundation of the Japanese business culture. In Summer 2020, Philip Patrick, lecturer at Tokyo university and contributing writer at the Japan Times, wrote for the Spectator about how government grants in Japan to support working from home could lead in part to a breakdown in the deferential and devotional organisational culture in Japan, while potentially allowing it to open up more to foreign involvement:

According to the business lobby Keidanren (Japan’s CBI) 66 per cent of respondent companies had initiated teleworking, and a recent survey found 70 per cent who had worked remotely during the lockdown were either very, or somewhat keen to continue doing so permanently.

Hibata Ōsuke (possibly), detail from The Mission of Commodore Perry to Japan in 1854, 1854-58. As a result of this mission, on 31st March 1854 the Treaty of Kanagawa was signed between the US mission and the Shogunal representatives, opening two ports and ending Japan’s self-imposed restrictions on contact with the West.

Or Do Traditions Allow You to Remain?

Changes to the keiretsu structures were instituted through corporate governance reform through the 1990s to help ameliorate the effects of this lost decade; regulatory changes thus required the appointment of an independent auditor to the board, with many companies simultaneously appointing increased numbers of international executives. This came to the forefront prominently with Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, the largest of its kind in Asia, under its president Yasuchika Hasegawa. During his time as president – he is currently chairman of the board – Hasegawa altered the focus of the company entirely, created an advisory board consisting of international members. Additionally, on the main executive board, he reduced its numbers while adding individuals who have few cultural connections to Japan itself, moving towards a more job-oriented Western idea of recruitment and performance.

As of November 2021, we have just been shown perhaps the biggest indicator so far that Japan has broken away from its keiretsu infrastructure: the plan by Toshiba to split into three separate companies. This comes after a wave of scandals spurred activist shareholders into voting in favour of a radical overhaul of the current governance structure. Japan has had a paramount dislike for foreign direct investment for decades, being ranked by the UN Conference on Trade and Development as having the lowest ratio of inward FDI to GDP among all the 196 countries. This move therefore marks a key point in the country’s economic development as an historic instance of foreign shareholders coming out on top in a country so hostile to foreign interference.

The keiretsu groups were created because of foreign interference in Japan’s affairs, and it is becoming increasingly likely that they will deteriorate at the same hands. Whether this will be a good thing for Japan, or indeed for international trade, is still yet to be seen, but it will almost certainly alter the cultural and economic landscape of the country for many years to come.

Utagawa Hiroshige, 8th station: Oiso from The Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō, 1833-34.

Let's go home, let's go home, to that house in the countryside

Let's go back to the blue sky, the white clouds, in the countryside

Hako Yamasaki, Nostalgia

Closing your eyes isn't going to change anything. Nothing's going to disappear just because you can't see what's going on. In fact, things will even be worse the next time you open your eyes. That's the kind of world we live in.

Haruki Murakami, Kafka on the Shore

Until we speak again,

AJP

Beautiful Japanese prints Adam! I have a lovely reproduction print in my living room, 'Autumn Sky at Chōkō' (Chōkō shūsei), from the series Eight Views of the Ryūkyū Islands (Ryūkyū hakkei)

ca. 1832. Wrath of Gnon once kindly translated the calligraphy in the upper right corner: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/49940