Simulation and the Metaverse

A ruse by any other name ...

M C Escher, “Double Planetoid”, 1949

But what if God himself can be simulated, that is to say can be reduced to signs that constitute faith? Then the whole system becomes weightless, it is no longer anything but a gigantic simulacrum - not unreal, but simulacrum, that is to say never exchanged for the real, but exchanged for itself, in an uninterrupted circuit without reference or circumference.

Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation

Origins of Simulation

When I was a teenager, specifically around the ages of seventeen to nineteen, I was obsessed with the idea that we were, or, more correctly, I was, living in a simulation. My view then was not that this simulation was created for malign purposes, like in The Matrix or some other similar science fiction creation. Rather, I had the view that it was a form of research for some higher civilisation, a way for them to rewind time - their past - and see what lay there. In this case, it was humanity.

This viewpoint stemmed from a paper I read around this time from contemporary Swedish-born philosopher and theoretical physicist Nick Bostrom entitled “Are You Living In A Computer Simulation?”, which became popularly referred to as the “Simulation Argument”. The paper is relatively short - only twelve pages - and is fleshed out with some intimidating looking calculations which in reality are relatively pointless modes of confirmation bias. Nevertheless, I was convinced by the hypothesis of the paper, as outlined here, in its abstract:

This paper argues that at least one of the following propositions is true: (1) the human species is very likely to go extinct before reaching a “posthuman” stage; (2) any posthuman civilization is extremely unlikely to run a significant number of simulations of their evolutionary history (or variations thereof); (3) we are almost certainly living in a computer simulation. It follows that the belief that there is a significant chance that we will one day become posthumans who run ancestor‐simulations is false, unless we are currently living in a simulation.

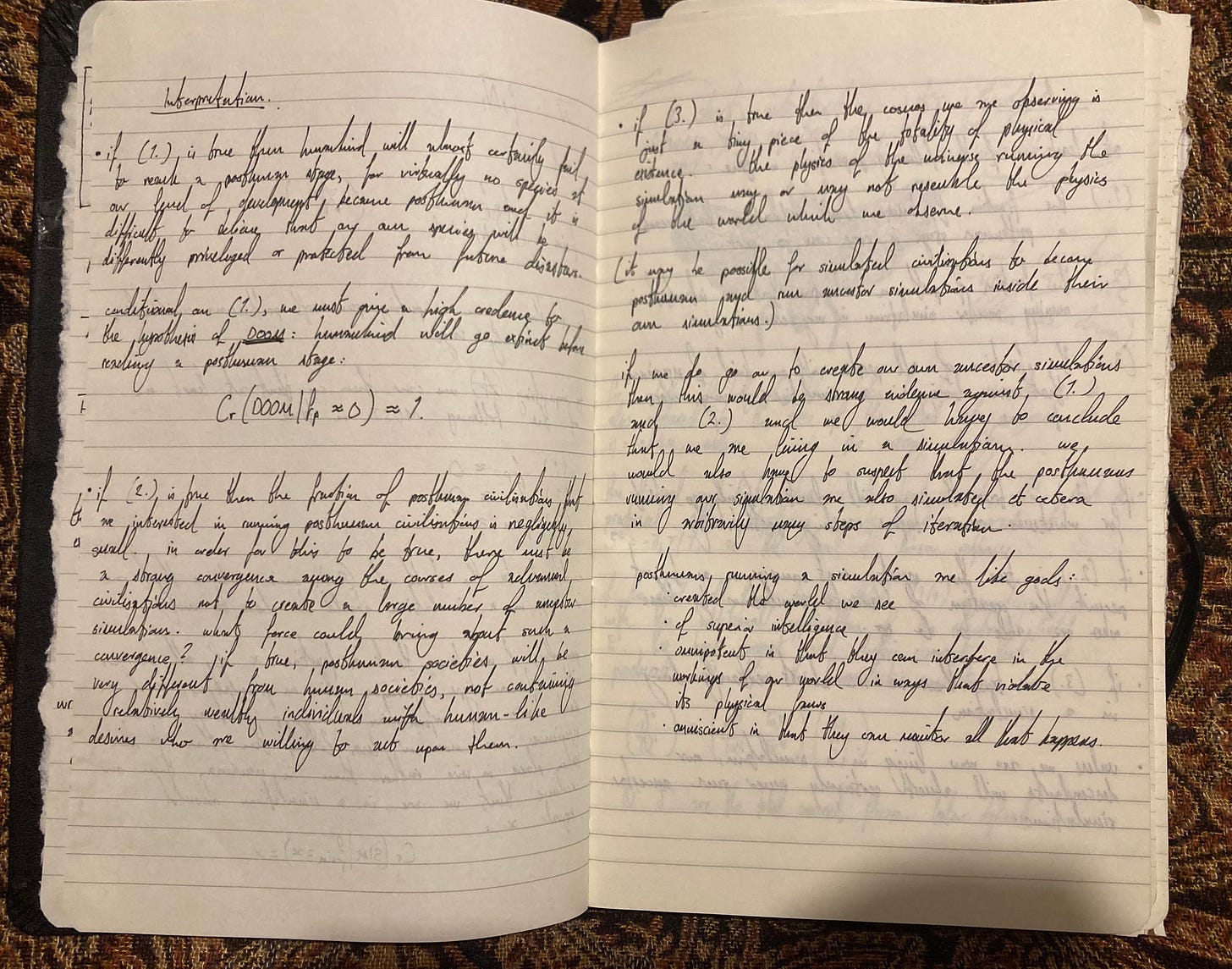

As I was a hopeful young man, enraptured by the seemingly infinite prospects of technological development in the future (how naive), I could not possibly fathom humanity going extinct before it reached this “posthuman” stage, and so believed the simulation argument to be true. As I did with many things I wished to learn, I copied the entirety of the paper into my journal at that time by hand, as this is how I remember things. I have a photographic memory, but only with things I have produced (or reproduced).

Part of my reproduced version of the paper.

As I got older and realised that technology was almost certainly going to be humanity’s downfall rather than the path to its apotheosis, I realised that this paper was mostly without truth. But it did, however, plant the seed of thought that this idea of a simulation may be attempted, if not successfully created.

And What of the Star Maker?

I had recently caught wind of a recommendation on Twitter from user Mencius Moldbugman to read a book named Star Maker by Olaf Stapledon, published in 1937. It is not often I see something referred to as “the greatest book I’ve ever read” and not be at least slightly interested. So I purchased the book, read it, and can confirm it is quite fantastic. But one part peaked my interest in particular — a short, inconsequential section describing a facet of an alien world not unlike earth:

During my last years on the Other Earth a system was invented by which a man could retire to bed for life and spend all his time receiving radio programmes. His nourishment and all his bodily functions were attended to by doctors and nurses attached to the Broadcasting Authority … Participation in the scheme was at first an expensive luxury, but its inventors hoped to make it at no distant date available to all. It was even expected that in time medical and menial attendants would cease to be necessary.

This got me thinking back to the Simulation Argument, back to my first time watching The Matrix and the succulent-but-not-real steak, and I was shocked for a moment. After taking a moment to connect all of these vague cultural ideas in my head, I continued reading:

Programmes of all the most luscious or piquant experiences were broadcast in all countries … Thus even the labourer and the factory hand could have the pleasures of a banquet without expense … In an ice-bound northern home he could bask on tropical beaches …

By this point, I could see where this was going, and something written almost a century as fantasy was being linked to future possibilities in the real world, and an unescapable horror along with them:

Governments soon discovered that the new invention gave them a cheap and effective kind of power over their subjects. Slum-conditions could be tolerated if there was an unfailing supply of illusory luxury. Reforms distasteful to the authorities could be shelved if they could be represented as inimical to the national radio system. Strikes and riots could often be broken by the mere threat to close down the broadcasting system.

I felt no longer as if I was reading science fiction. It felt prophetic.

Welcome to the Metaverse!

Facebook and Meta founder Mark Zuckerberg wearing a human suit

Recently, Facebook announced its rebranding to Meta, a move signalling its commitment to building “the metaverse”, which so far appears to be a glorified virtual reality Microsoft Teams with PlayStation 1 graphics (Microsoft is also intending to build its own “metaverse”). But, as with seemingly everything that the big tech companies have released in recent years, it is viewed as wonderful, progressive, and a way to make life easier. After all, working online is a key part of the New Normal.

But like all of Zuckerberg’s creations to date, it is improbable that this metaverse won’t spiral out of control at some point, taking on a new life as something entirely other. Do you remember when Facebook was just a fun way to share photos with your friends? Or how about when Instagram didn’t give young girls mental illnesses and eating disorders? If the metaverse is as widely adopted as the mainstream culture would have you imagine it to be, then it is almost certain that it will end up being used for more than just work meetings.

Personally, I do not want to spend more time in a virtual world. Since I started my current job less than two months ago which requires looking at a computer screen for at least eight hours per day, I have experienced more headaches than I have in the rest of my life combined. Physical health problems are only one part of this; mental health problems are arguably more common, and I can imagine these would increase if it is considered normal to wear goggles which project blue light directly into your retinas for the majority of your waking hours.

We do not need another simulation.

The old slogan “truth is stranger than fiction,” that still corresponded to the surrealist phase of this estheticisation of life, is obsolete. There is no more fiction that life could possibly confront, even victoriously - it is reality itself that disappears utterly in the game of reality - radical disenchantment, the cool and cybernetic phase following the hot stage of fantasy.

Jean Baudrillard, Simulations

Take care,

AJP

Keep going!

Jean Baudrillard was such a card. FAMOUS for book called: Simulacre and simulation.

FROM WICKI "The simulacrum is never that which conceals the truth—it is the truth which conceals that there is none. The simulacrum is true."

— The quote is credited to Ecclesiastes, but the words do not occur there. It can be seen as an addition,[4][5] a paraphrase and an endorsement of Ecclesiastes' condemnation[6] of the pursuit of wisdom as folly and a 'chasing after wind.'

Personally I love the chase the wind part. Hail to the feast. Above and beyond.